Tom Carr describes his artwork as a synthesis of photography and archaeology. He has lived in Colorado since 1993 and has exhibited his work across the state at numerous civic and commercial venues, including the Denver Public Library, Dairy Center in Boulder, Open Shutter in Durango, the University of Denver Museum of Anthropology, Fort Lewis College, and the Ute Museum in Montrose. Our personal relationship dates to 2007, when I visited (Real) Photographic Constructs at the Center for Visual Art in Denver, which Tom helped curate for the Colorado Photographic Arts Center. For me, it was a transformational exhibition that encouraged my involvement with CPAC and with photography in Colorado in general. Most recently, it was a treat to see Tom at the “Framing Place and Time” gathering in Trinidad, Colorado, where he orchestrated the iconographic group photo above.

This recording was made February 25, 2022 at Tom’s home. It has been edited and shortened from the original for this post.

RJ: Can we begin by talking about your background?

TC: I first came out in November of '92 to interview with the graduate studies' department at CU Boulder, in the anthropology department. I was accepted, moved here in June of 1993 from North Carolina, and started graduate school in the Fall of '93. I'm an anthropologist by profession, archeologist specifically, and I've been doing that since I got interested in 1986.

I remember being between the ages of ten and twelve and being interested in science and art, and thinking that's what I want to do. I just loved to explore. I think exploration is the biggest part of what drives me, understanding the history of the land - I always used to joke that I wanted to be a xeno-archaeologist, doing archeology of other planets, of other civilizations.

Pawley’s Island, 1983

My dad picked up a 1950's era 35-millimeter German camera, a Baldina, and he let me start using it in 1976. It had film advance problems, but I started shooting black-and-white and color photos. Then I saved up pretty quickly and bought my first 35-millimeter camera with interchangeable lenses and started developing film in 1978. I was thirteen or fourteen now, and I had an older cousin, my mom's cousin, who owned a photography studio in Ohio. He showed me how to process film, print my pictures, and he just turned me loose in his darkroom for a month.

Moon and Clouds over the Atlantic, C-Print, 1980

I did a lot of things with long exposures and lights and movement and stuff like that. Some of that got into these Scholastic Art exhibitions in 1981 and 1982. I got a nomination for a Kodak medallion of excellence for this image here (left). And then I entered into this thing called the National Foundation for Advancement in the Arts, and I won an award Promising Young Artist in Visual Art.

When I first started in college I went into fine arts and photography. I had an exhibit called "Winter Scenes from a Greenway Park" in 1984. It was a formal black and white study of McAlpine Creek Park and subsequently I photographed spring, summer, and fall as well.

I found this tenant farmhouse that later became the focus of my undergraduate work. The Norcutt House was a 1922 tenant house built after the property was broken up after the Civil War. I made a film about it called A Forgotten Place: The History of an Abandoned Farming Community. [2]

Above, L-R, Top Row: Cloud and Tree, 1983; McAlpine Creek, 1984; McAlpine Creek, 1984; Bottom Row: Robinson Rock House, 1986; Ohio, 1987; Norcutt House, 1988.

Ten years later in 1998-99, when I was in grad school at CU Boulder, I took a year-long sequence in ethnographic film, and that's when I made the film (in 2000). I structured the film as a telling of the history of finding the house, documenting the house, conducting the interviews, taking the third-generation descendants back to the house, and then getting their thoughts on how memory and history can bring family together, and how we're so disconnected from it in so many ways. At the CU Boulder Anthropology Department premiere, Paul Shankman, one of the ethnography professors, said, "Tom, this is Errol Morris meets The Blair Witch!" It was shown in three different film festivals, and it's in a bunch of libraries around the country.

I was working on a PhD, and working on this project, and I was TA-ing for classes and stuff like that too. I would do archeology projects in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho and New Mexico and Utah. They were either university projects or my own projects, but I would always take photographs everywhere I went. I did a little show in the Anthropology department that I called Restless Spirits (September 1995–June 1996). I'd also been asked to set up the department’s darkroom. So, I set up the darkroom, nobody else was using it so I used it all the time. That's where that was printed. I did all the research for my PhD, but I was having such a hard time with my PhD that I ended up having to bail on it. That's a whole other story.

Top Row: Fort Laramie, 1994; Farview House, 1995; Lemhi Valley, 2002; Hovenweep, 2005. Lower images: from Conflict on the Plains, 2007.

For a while I did contract archeology from 1999 to the beginning of 2001, when I got a job as a staff archeologist for the State of Colorado. One of the things I had started reading about was the co-evolution of photography and archeology as young, new sciences. Some early archeologist antiquarians picked up photography as a way to make a record of their studies. People like Maxime Du Camp and Eugene Greene—even Talbolt, apparently—would take photographs of their own archeological expeditions.

At first, I thought I'd discovered something, then I'm like “no, no, people have been noticing this for a long time.” So, I wrote an article about it, but I Colorado-ized it. I connected it to Jesse Nussbaum, who was originally a photographer studying at Greeley [who] went on to become an archeologist and the first superintendent of Mesa Verde National Park. He took beautiful 7 x 7 inch negative photographs. We included him in a Mesa Verde exhibit we did in 2006 at History Colorado.

This was the time when I felt I was getting some traction with my work. Colorado Heritage magazine used one of my photos from Mesa Verde on the cover and I was invited to do an exhibit in Durango, at the Center of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College (2004.) [3] After that, it went to the Farmington Museum and then the Canyons of the Ancients visitor center. So, it had two-and-a-half years of exhibition.

When I worked for the state, I was on the State Contingent to the Park Service and the Tribes for helping designate the Sand Creek Massacre Site. So I became very interested in it and I learned a lot about it. And then I decided I wanted to learn more about some of the other places. I don't know exactly how this happened, but an artist named Lee Lee, who was a painter here in Denver, curated an exhibit about genocide at the Mizel Museum (‘Glocal’: Artists Interpret Genocide, 2007).

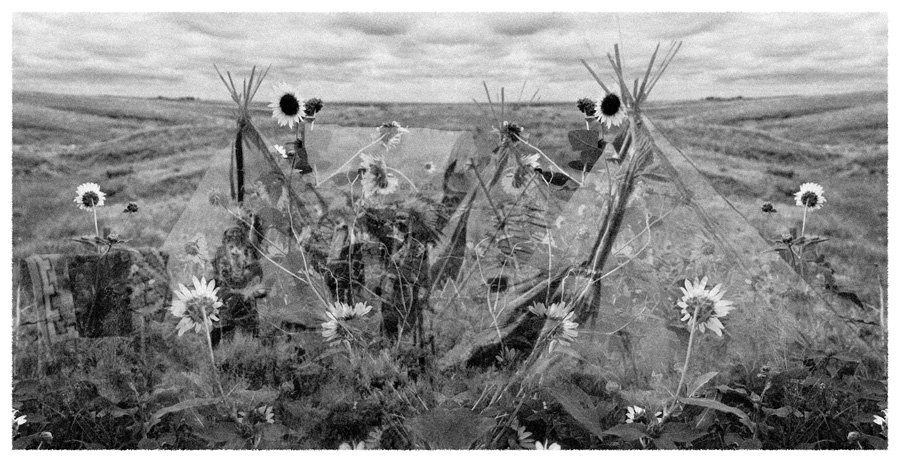

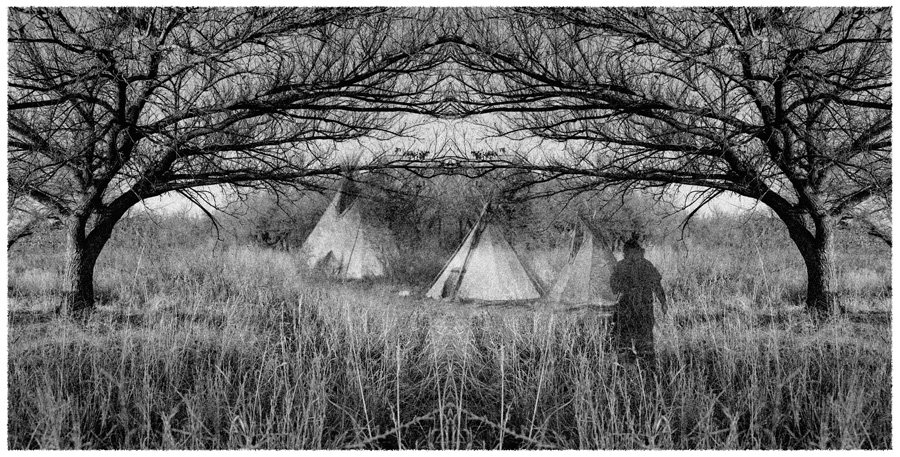

I was one of ten local artists she asked to create a body of work. I had this idea that my wife helped me with, to use my photographs and historic photographs in tandem (Conflict on the Plains). At the time I was mostly still shooting with my Rolliflex, and every single photograph for this whole series I took like it was half an image. I knew that I was going to mirror it and then blend it with a historic photo, to create this faux landscape effect. Some people love it, some people hate it. I actually had one person who came up to me and said, "Great lecture, but I hate that mirroring thing." And I was like, "Okay." [Laughs]

Top Row: from Excavating Childhood, 2010; Bottom Row: from Expeditions, 2015

In 2015 Jim Krall invited me to do a big exhibit at the Denver Public Library. That was called Thomas Carr: Expeditions. Around the same time, a project that I had started called Excavating Childhood was starting to get some attention. I was visiting my childhood home in 2008. A storm had washed out a big swath of the backyard [and] there were plastic model parts washing up. [When I was a kid] I would set them on fire and blow them up and take pictures. I found my photographs and old drawings from the 1970s, and started making these composites of old negatives, drawings, and photographs, mixing them all together. I did the series primarily in 2008, 2009, then it just sat there. But just before I left History Colorado in 2015, they did a toy exhibit. Somebody had heard me tell this story about finding the toys, so I wrote it up and Colorado Public Radio called me and invited me to do an interview. You can still listen to it. It was so fun. And that was the last thing I did before I left History Colorado.

RJ: Subsequently, you’ve done a lot of work with the homeless, in camps you’ve discovered while working.

TC: When I left my employment with the state, I started getting back into doing contract archeology, which involves doing surveys of ahead of development projects. I had encountered a homeless camp in the late nineties on one of those projects and it had this sign with a hierarchy of rules that reads like “Welcome to the Hobo Jungle.” And I was just intrigued. I knew of some archeologists who had studied homeless camps [and] when I was doing contract work along the Front Range urban corridor I would find a homeless camp on almost every project that I went on. I didn’t have the means to do a full cultural study, but I could do a visual ethnography because it combines my photography anthropology interests. And so I spent three years visiting sites, and since I was self-employed I could just do it on my own time.

I encountered the temporary homeless, the long term homeless, the employed homeless, the unemployed homeless, the people, the range of reasons that resulted in it—drugs, other addictions, alcoholism, medical issues, mental health issues, and just the simple reality that it is getting so hard to make a living wage. I just did it as a philanthropic thing, just for the greater good.

I estimated I visited about eighty camps over three years. Half occupied, half unoccupied. I talked to about fifty people. About half were okay with me talking about their story. Then out of those twenty-five, only about fifteen were comfortable with being on camera. Maybe a little more. A lot of people, the homeless, of course were still very stigmatized, very ostracized. But even as an anthropologist, even knowing about keeping an open mind and being understanding about subcultures and countercultures and the way that society disenfranchises people, I still had a little bit of a discomfort with it at first.

At the time, I had been laid off by the state and we had to find a new place to live. I was feeling it on a personal level and dedicating a lot of time and energy to this project. We had the exhibit at 40 West and then we had the exhibit at the University of Denver's Museum of Anthropology (Traces of Home, 2018). As a matter of fact, somebody from the city recently contacted me. I’ve got a whole portfolio of prints that I'm going to share with them.

RJ: What are they going to do with that?

TC: I think they're going to use them in the office, and they might do something else (note – there’s been no additional progress on this.) A place called The Action Center did a pop up and I had a few sales. I donated half to the Center and then, of course, I had spent several thousand dollars in making the exhibit happen, so I lost slightly less money. It keeps rolling. I mean, I did the popup and met a researcher at DU who's with the Center for Housing and Homelessness. I keep it alive in that respect.

The next big thing that I really need to start thinking about is that we don't even look at prints. You know what I mean? We don't have to. You see it. But I have thousands of prints because I believe that for it to really exist, I’ve got to make a print. I make hundreds of prints of everything, not of every exposure, but every time I feel like this is important, there needs to be a print.

END

(Below, L-R: from Places in Between, 2020, 2021, 2021.)

All photos courtesy of Thomas Carr. https://thomascarrphotography.com/

1. Image by Thomas Carr. Back Row, L-R: Rupert Jenkins, Mark Sink, Julie Stephenson, Krystle Stricklin, Kevin Smith, David Freund, Melissa Totten, Miles Scott. Next down, L-R: Mark Klett, Linda Connor, Richard Neill, Willy Sutton, Scott McLeod. Next down, L-R: Marshall Mayer behind Bonnie Lambert; Kenda North, Caroline Hinkley, Gary Emrich, JoAnn Verburg, Robert Dawson (behind Kenda North); Seated L-R: Mark Johnstone, Wanda Hammerbeck, Darryl Curran, Greg Mac Gregor; Standing next to Greg: Ellen Manchester, Tom Lamb (behind), Tom Carr. On steps, T-B: Keith Farley, Jim Stone, Barbara Houghton, Jay di Lorenzo, Vickie Lamb.

2. https://www.archaeologychannel.org/video-guide-summary/243-a-forgotten-place-the-history-of-an-abandoned-farming-community

3. Presence Within Abandonment: Photography, Archaeology, and Western Historic Sites, 2004.

The Colorado Photo History blog is the online presence for “Outside Influence,” a book project by Rupert Jenkins. As always, please leave a comment or a suggestion for future posts, and visit @coloradophotohistory on Instagram.

#coloradophotohistory @coloradophotohistory #outsideinfluence @cophoto2022 @cpacphoto #coloradophotographicartscenter @thomas_carr_photography #thomascarrphotography