Colorado’s elder statesman of photography, James O. (Jim) Milmoe, passed away at his home in Golden, CO, late December 2022. He was ninety-five years of age. A memorial service honoring Jim will be held on Feb 27th at Mt Olivet (12801 W. 44th Avenue, Wheatridge, Colo). Service at 11:30 am, with a Celebration of Life at the Arvada Center from 3:30-6:30 pm.

This month’s post is dedicated to Jim and his surviving family. It begins with a description of Jim’s interactions with five other Colorado photographers in the early 1950s who were each linked to the photographer Minor White—perhaps the most influential proponent of fine art photography in the U.S. at the time. It concludes with a brief overview of his educational achievements, and his career-long project photographing grave markers, which was published as “The Art of Grave Markers” just weeks before he passed. A two-part interview with Jim was posted on this site February and March 2022. Please use the blog search engine to access those posts.

Rupert Jenkins

“An era of importance in contemporary photography … began in the early 1950s in Denver when a small group of young men were bonded for a few years by the mutual use of photography as a creative medium for personal expression. … The photographer Minor White was a connection, as we each had a separate link with him.” Nile Root [1]

In December 2005, Denver’s Gallery Sink presented Early Colorado Contemporary Photography—a remembrance and revival of Winter Prather, Jim Milmoe, Walter Chappell, Arnold Gassan, Nile Root, and Syl Labrot. The show was one of the first events I researched when I began this history of photography project in 2017. To that end, I turned first to Mark Sink, the owner of Gallery Sink, who had structured the show around Jim Milmoe’s personal photography collection, which included vintage prints by all of the group. I also conducted the first of several lengthy interviews with Jim, who at the time was the only surviving member of the “small group of young men,” as Root termed them.

Nile Root’ serving customers in his Photography Workshop camera store on East Colfax Avenue, Denver. The store served as a base for the Minor White group during the 1950s.

One of the first things I discovered in my research is that dates are invariably vague, and accounts vary. Nowhere is this more true than in the history of the so-called “Minor White Group” in Denver. Arnold Gassan wrote copiously about his experiences as a fledgling photographer in Denver at the time, and Walter Chappell also reflected on the era at length in various interviews and essays. Labrot fails to mention a group in Denver at all in interviews I’ve accessed; Root is quite specific about some activities yet vague on others.

Milmoe, then, was obviously the most tangible remaining link to the group and the era; nonetheless, he emerged as one of several “unreliable narrators” whose recollections were often at odds. For instance, whereas Gassan and Chappell place themselves, Winter Prather, and Nile Root as the group’s core participants, Milmoe’s recollection is that it “started with Winter, Nile, and me.”

Although each group participant was aligned with Minor White, their actual interactions relied on correspondence and portfolio critiques by mail. Chappell had befriended White in Oregon in 1941, and was their closest connection to him. Gassan writes of them send packages of prints to White, who would return them with comments. Prather was something of a technical genius, and he undoubtedly taught Chappell and Gassan how to print, most likely at Root’s Photography Workshop camera store on Colfax, which provided a meeting place and housed a darkroom.

Above, Top Row: Nile Root, c. 1960; James Milmoe, 1962 (Polaroid taken at the Minor White workshop); Winter Prather, c. 1950s. Bottom Row: Walter Chappell, c. 1955; Arnold Gassan, c. 1958; Syl Labrot, c. 1960.

Prather and Milmoe had an interesting relationship. They were both commercial photographers whose activities occasionally crossed over, as when Prather (not uncommonly) failed to show up for a shoot at the Coors brewery in Golden. During one of our interviews, Jim described the situation: “Winter was doing some commercial work here in Denver and one day he had a shoot scheduled with Coors. He was supposed to come by at 10 am to shoot, and no Winter. So Whitey Edens [Coors art director] called him up and said, ‘Winter, what happened you were supposed to be here at 10 o’clock,’ and Winter said, ‘Aww, I got up this morning and I didn’t feel like taking pictures.’ Well, needless to say, that was the end of Winter and Coors. So I started working with Coors and I shot for them and did a book.”

I asked Jim if Winter had been mad at him for taking his job? “No, no, no,” he replied, “We were good friends, he didn’t care, he didn’t want to do it. [After that] he went to New York and shot for one of the airlines and others, and got in trouble with those guys.” “Those guys” were Chappell and Syl Labrot. The two had relocated from Denver to Rochester and Connecticut respectively, in 1957 and 1958. The deep relationship between Chappell and White was such that he joined White in Rochester as assistant editor for Aperture magazine, and took over White’s former curatorial duties at the George Eastman House Museum (GEH), working under its director Beaumont Newhall, and alongside Nathan Lyons, who had taken over White’s editorial duties.

Reflecting on his interactions with Labrot, Milmoe recalled that before he left Denver Labrot was starting to do dye transfers, which he and Prather also practiced: “I don’t know where I met Syl but he was just starting out in commercial photography and he was doing postcards—little red barn and mountains in the background, snow, good but very commercial—and I said, ‘Syl, you’ve got to come down and meet these guys, we’re doing interesting work and you should see it.’ So he came down and he did a 360! And that’s what started him on really creative stuff and he just took it and ran.”

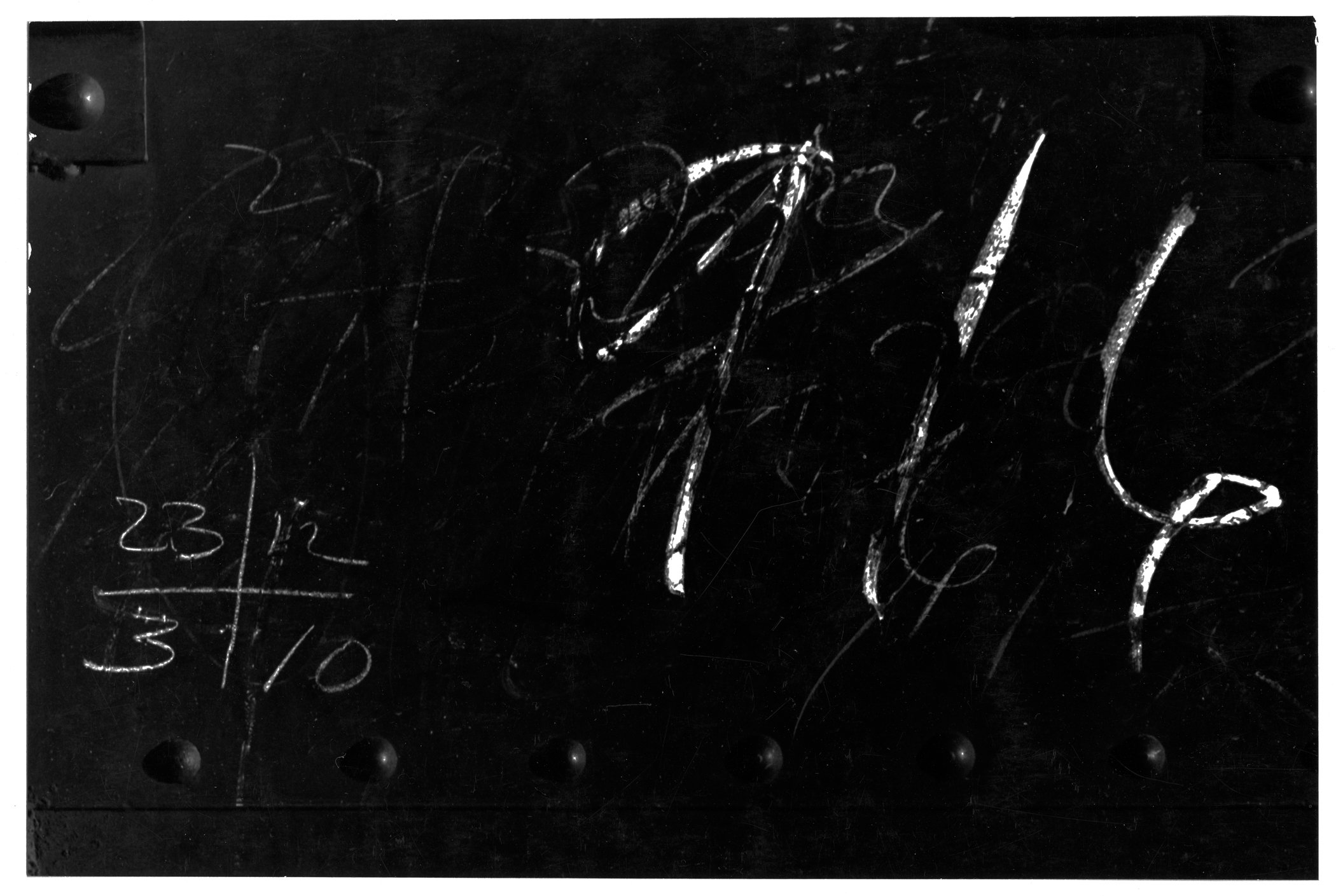

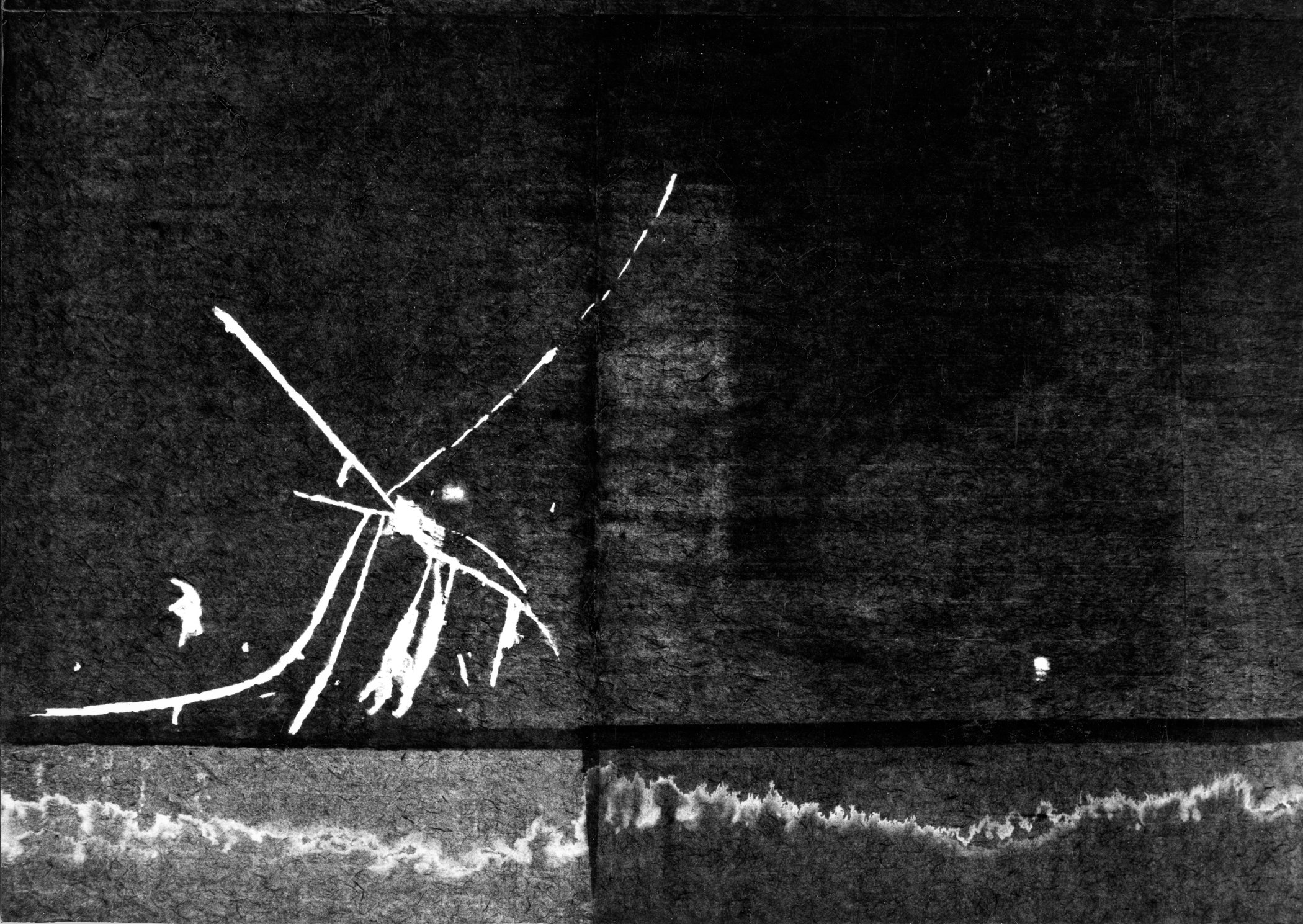

Notation of a lesson from the first Minor White workshop, by Arnold Gassan. Source: “REPORT: minor white workshops and a dialog failed,” in CAMERA LUCIDA: The Journal of Photographic Criticism 6 & 7 (1983)

Milmoe met Minor White in person for the first time in 1962, when he attended the first of three Minor White workshops in Denver (1962, 63, and 64, hosted by Gassan). Nile Root’s nephew, Victor Proulx, who was sixteen at the time and living with Root, recalls how intense the workshop was for students: [They] would come in from having taken pictures all day and work like mad to get things ready for the presentation at night, which sometimes were in Golden [at Jim Milmoe’s house].

“I don’t think they got a lot of sleep. They would go to Central City to photograph, then come back down, develop negatives, print them, mount them, and then sometimes go back to Golden for the critiques. White had a lamp up in the corner of the room and students would put their picture under the lamp, and all lights were off except for the lamp, and you’d just sit there in quiet. Then there would be this critique.” [2]

White’s Zen-like approach to portfolio critiques perplexed Milmoe (as they did many people), but years later he realized they had had a profound influence on the way he “look[ed] at a thing, seeing it in total concentration … and relating to it visually, and sympathetically, empathetically.”

Jim Milmoe, 1978. Image by Barbara Houghton, from the “What We Wear” series.

Jim Milmoe spoke of three milestone accomplishments in the seventies that define his career: Ansel Adams citing his technical book “Guide to Good Exposure” as “the best instruction book for any exposure meter I have ever seen” (1970); his coup with the Denver Art Museum (1972); and a Governor’s Award “for his dedicated efforts in advancing the Arts and Humanities in the State of Colorado” (1973).

To that, I would add his extensive contributions to photo education in Colorado. In 1959 he wrote the curriculum for Colorado’s first photo degree program at the University of Colorado. Three years later, in response to his students lobbying for an academic component to enhance the practical tutorials, Milmoe developed an undergraduate History of Photography class that was offered for credit. With that, Milmoe relates, “I became the first photographer in Colorado to teach photography in a fine art department at the college level.”

During his career he taught at CU Boulder, Colorado College, Center of the Eye, and attended numerous symposiums, workshops, and conferences such as the Aspen Design Conference and the Colorado Mountain College July 4th workshops in Breckenridge. Despite his experience, however, Milmoe - like many of his generation - faced increasing competition from newly graduated photographers seeking teaching positions, so he decided to return to school and earn a MFA degree.

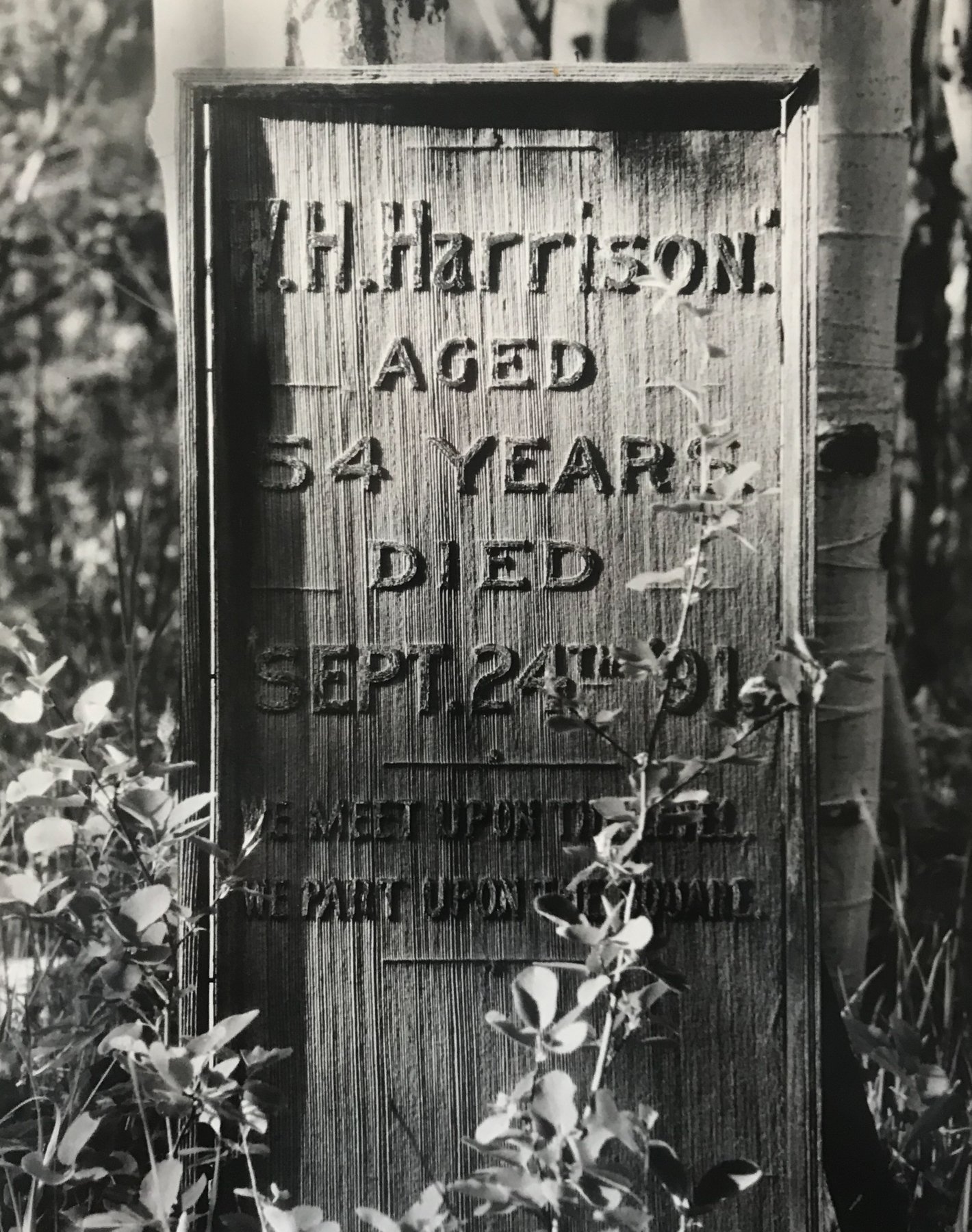

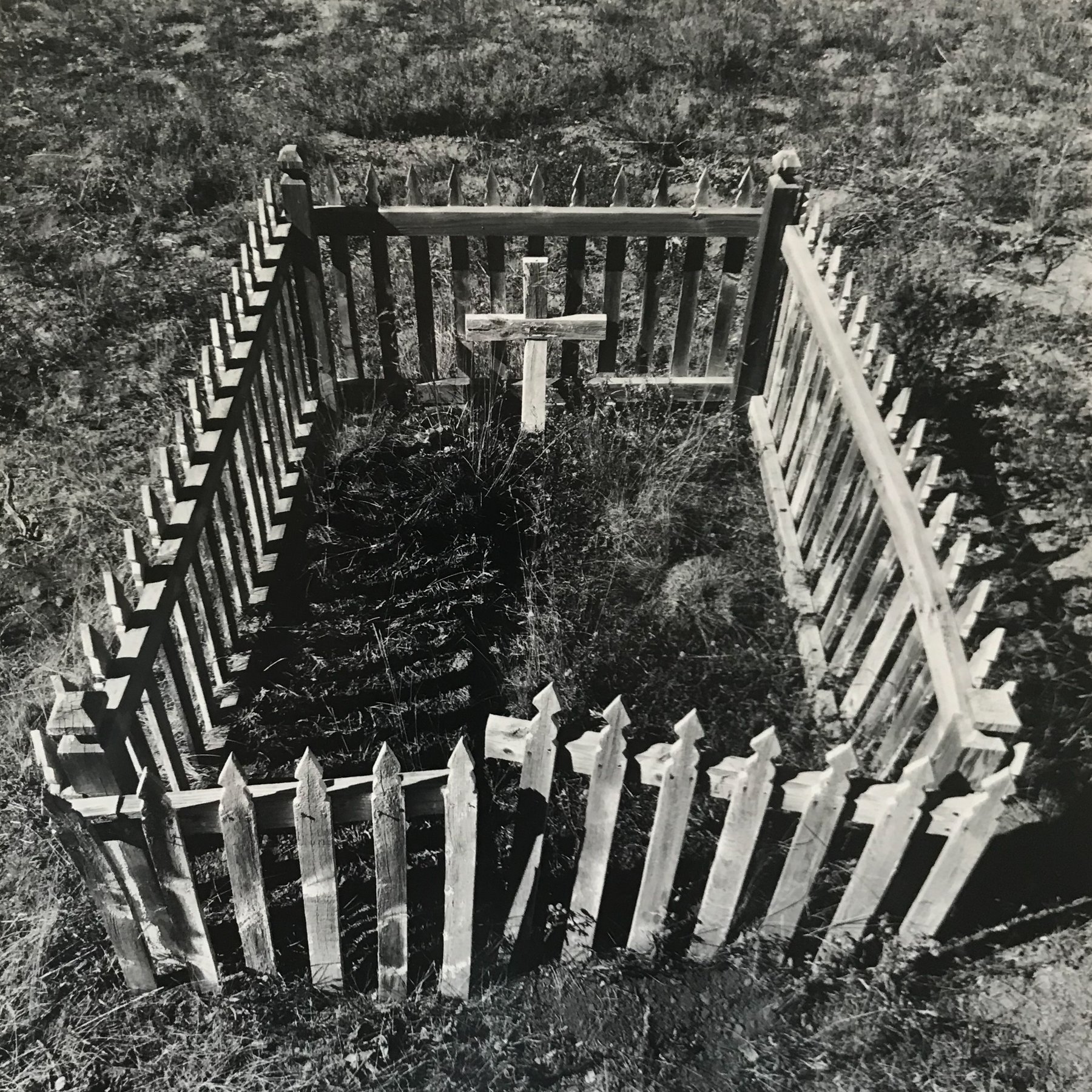

In 1978 he graduated from the University of Denver (DU) with a degree in photography and printmaking. He wrote his thesis on cemetery photography. [3] In 1989 the Denver Art Museum hosted his most prestigious exhibition, Shadows of Life: James Milmoe Photographs, which featured sixty-two images from his career-long documentation of graveyards. [4] In a letter to Milmoe written after the show closed, exhibition curator Dianne Vanderlip described the series as “one of the most important bodies of work ever produced by a Colorado photographer.”

During his later years, Jim’s impressive collection of books - many of them signed first editions and volumes on cemetery photography - was placed in DU’s Special Collections. After a pipe burst in his house, Jim spent months going through files, rescuing and collating negatives and contact sheets. He was a list-maker, constantly updating his records and gathering evidence of his notable legacy to photography in Colorado.

In late 2022, his own cemetery documentation was finally published in a book titled The Art of Grave Markers. The impressively printed and designed monograph was published in hardback by CPAC, the organization he had helped found sixty years earlier. At a book signing in the gallery, Jim appeared frail but was his usual hearty self, sporting as ever a unique bolo tie. Just weeks later, after a brief hospitalization, he passed away peacefully at home.

All Jim Milmoe quotes from personal interviews conducted January 2017, August 2018, and September 2018. A CV and gallery of Jim’s work can be found on his web site at jamesomilmoe.com.

[1] Nile Root, “My Early Acquaintance with David DeHarport, Winter Prather and Walter Chappell,” by Nile Root, January 2004.

[2] Personal interview, October 2017.

[3] “Cemeteries as a Source of Photographic Imagery”: A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Arts and Sciences, University of Denver [in] Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts [by] James Oliver Milmoe, June 1978. John B. Norman Jr. [Professor in Charge of Thesis].

[4] Shadows of Life: James Milmoe Photographs was shown at the DAM February 18–May 21, 1989.

Images above from The Art of Grave Markers, pub. 2022.