John Schoenwalter’s documentation of counter-cultural activities in Aspen and Denver spans almost a half-century. During his adolescence, Schoenwalter (1942–2019) was a traveler in search of direction. When we met at his studio in 2017, he recounted his childhood in New York City, where he worked in the family paint business “mixing five-gallon buckets of battleship gray … and lugging fifty-pound buckets … of red lead pigment to the mill.”[i]

I asked him if his father wanted him to take over the family business.

“Oh yes, yes. I graduated as a literature major from the Hebrew University. '63 got my first job in the garment district as a clerk for 75 bucks a week. I traveled across the country one year for a summer, and then another summer I went to Europe, hitchhiked for one month, bought a motorcycle and traveled around for three more months. When I came back, I started thinking I wanted to get away from New York.”

“That was in the early '70s. Bought a Dodge convertible for 500 bucks, put some of my possessions in there, after I told my mother I was moving out of the family business, and moved to Denver. A friend and my old roommate had talked a lot about Colorado, and that's why I came out here. I'd never been here before. I went to two places. Some young woman who had come to New York from Colorado said I should go to Aspen and Red Stone and Marble, which I did. I came back to Denver briefly, went back up to Aspen, rented a house with a guy I didn't know every well. I set up a gallery in the living room.”

Class at The Lower East Side Gallery, Aspen, ca. 1975. John Schoenwalter foreground, far left. Photographer unknown:

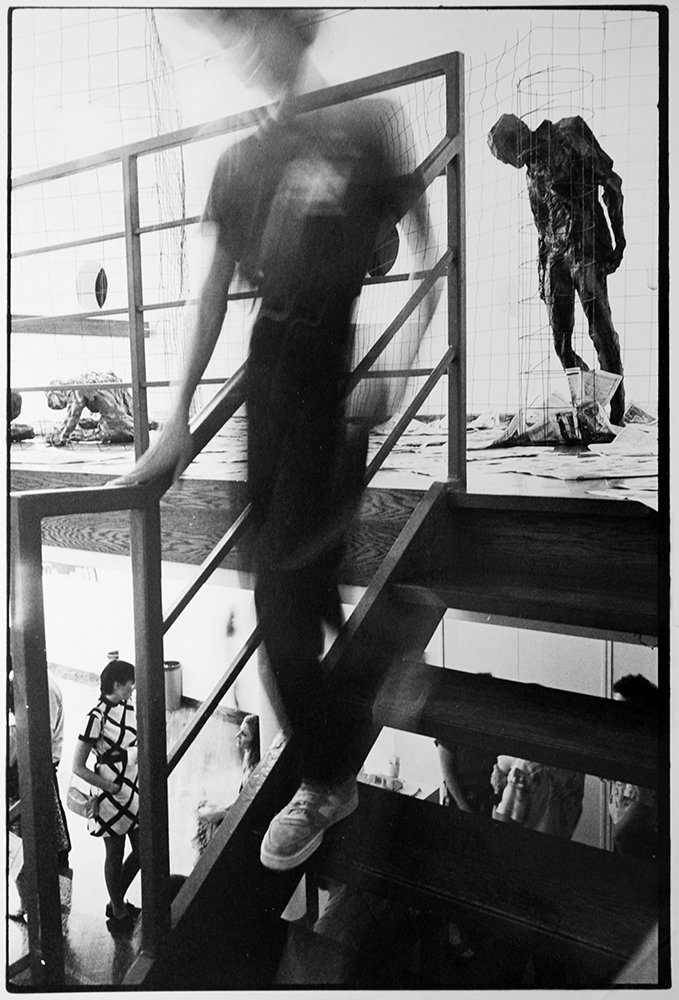

in 1972 he relocated his living room gallery to the basement of the Hotel Jerome—the space previously occupied by Cherie Hiser’s Center of the Eye photo workshop: “One of our housemates was a guy named George Peet, who was a teacher at the Center of the Eye photography school, which I'd never heard of before. I never really had a camera. George took me to the Center of the Eye and showed me darkrooms; I'd never seen a darkroom before, it was quite interesting. When the Center of the Eye was asked to move from the Hotel Jerome I went to the owner and I asked if I could rent the space. … I got the space, and people who were living out on the street helped me do demolition and rebuild. There was one guy who had some tools and knew how to use them, so I paid him. And we got a gallery built up.”

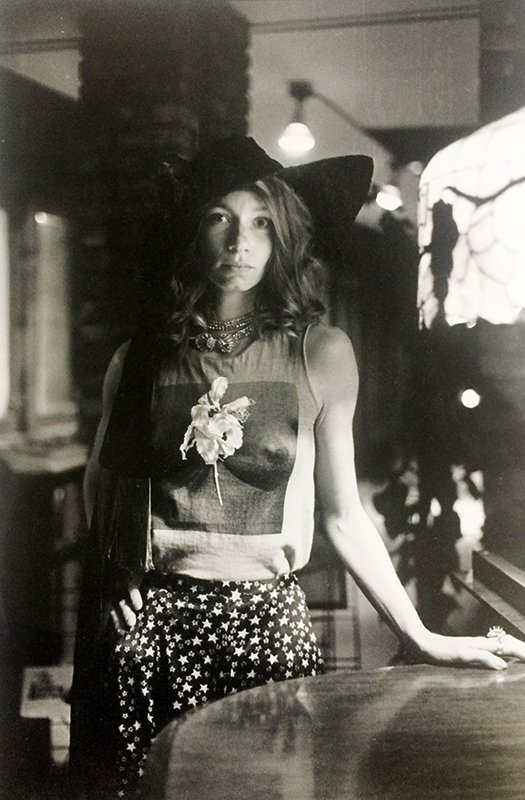

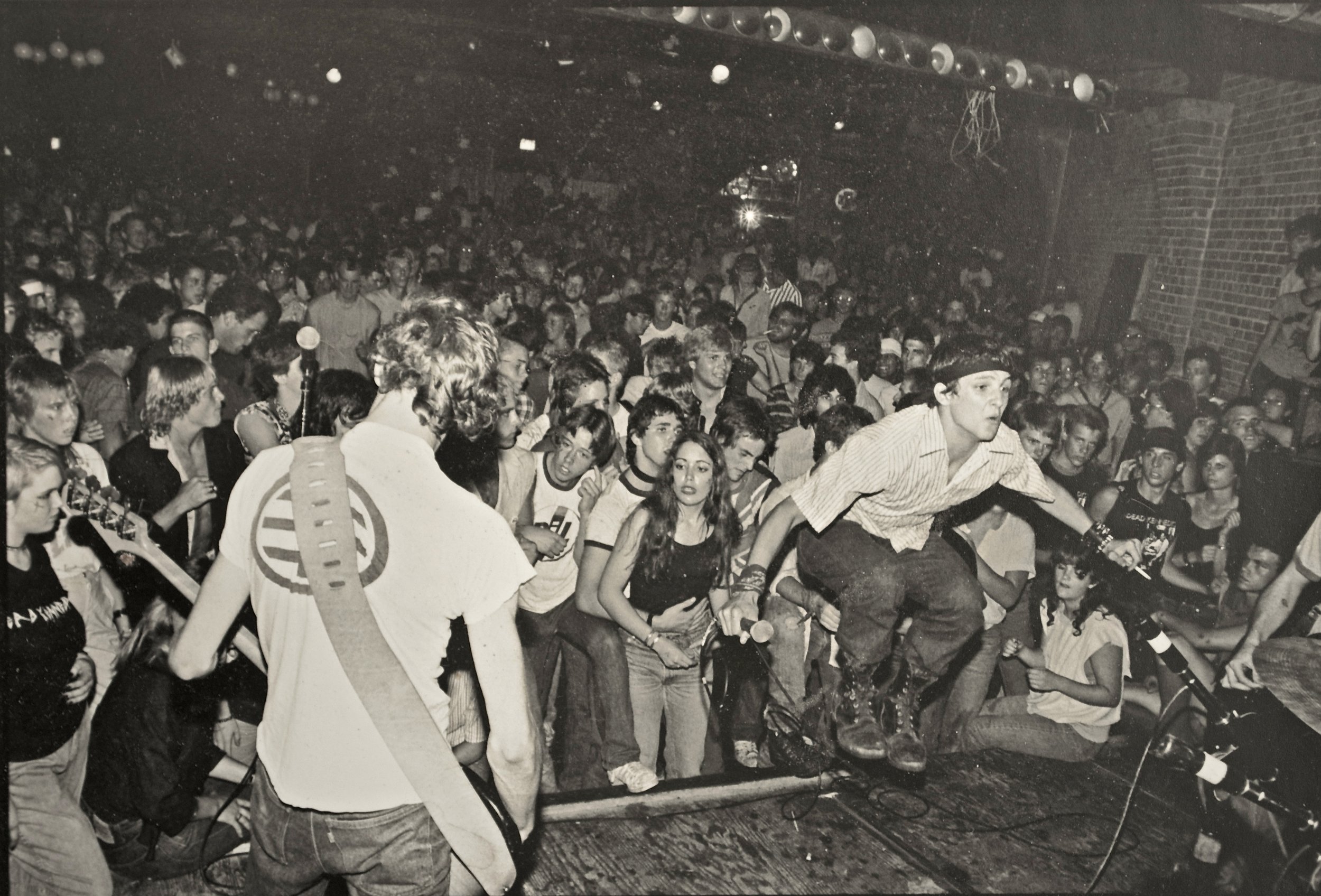

He named his space The Lower East Side Gallery because it was on the lower level of the hotel’s east side. There he exhibited painting, ceramics, and crafts, and also hosted workshops, poetry readings, life drawing sessions, and concerts during the summer. Schoenwalter took up photography to market the gallery and document events. The business held its own financially but in 1982 he closed it and moved to Denver, where he became a fixture at cultural events of all kinds.

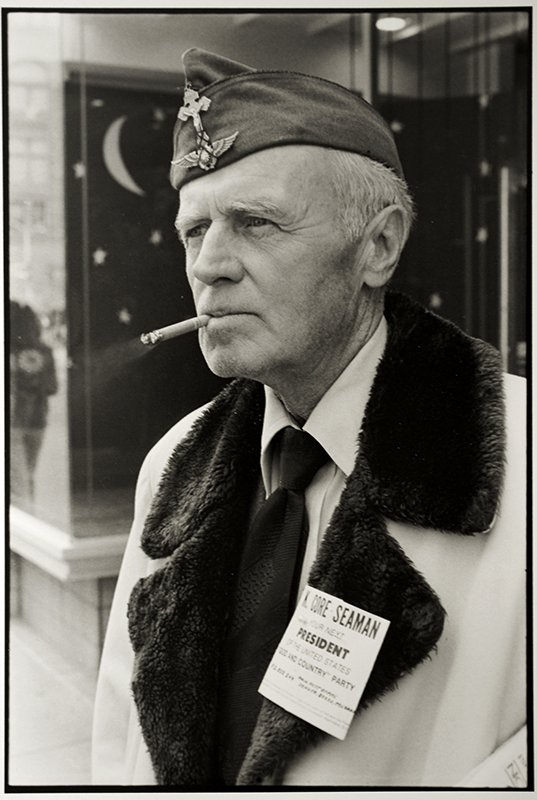

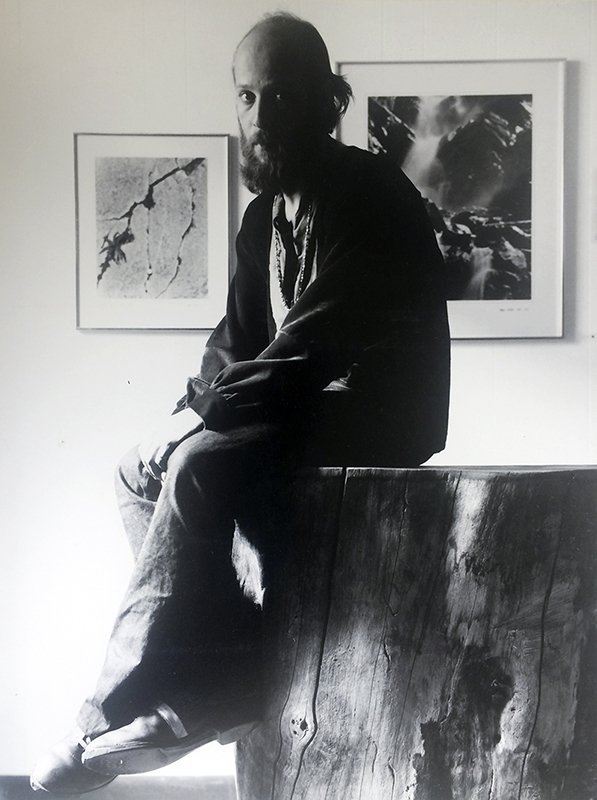

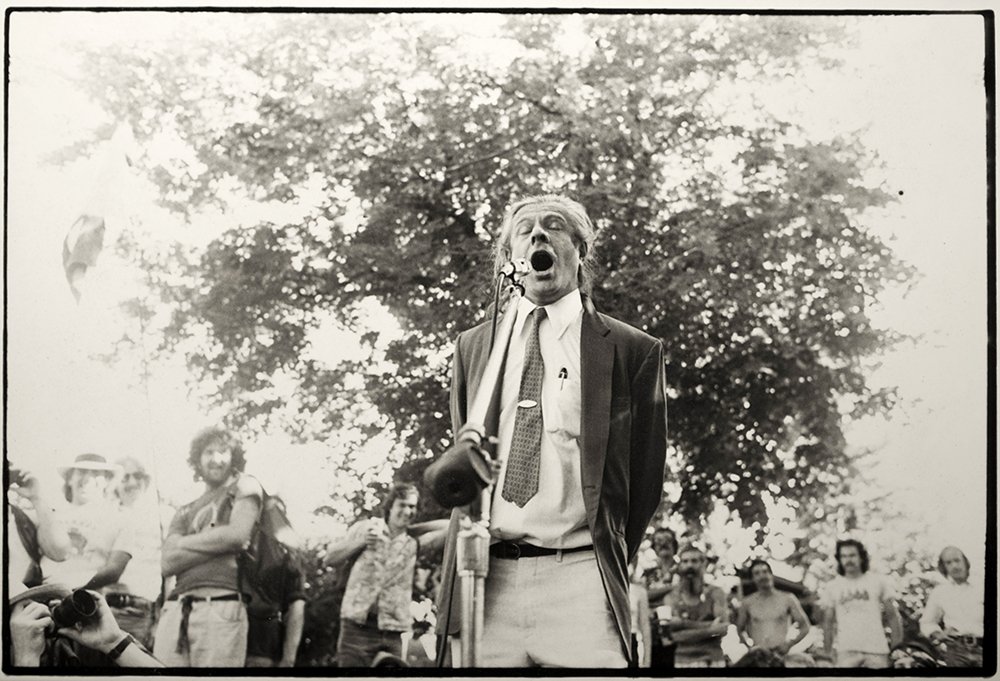

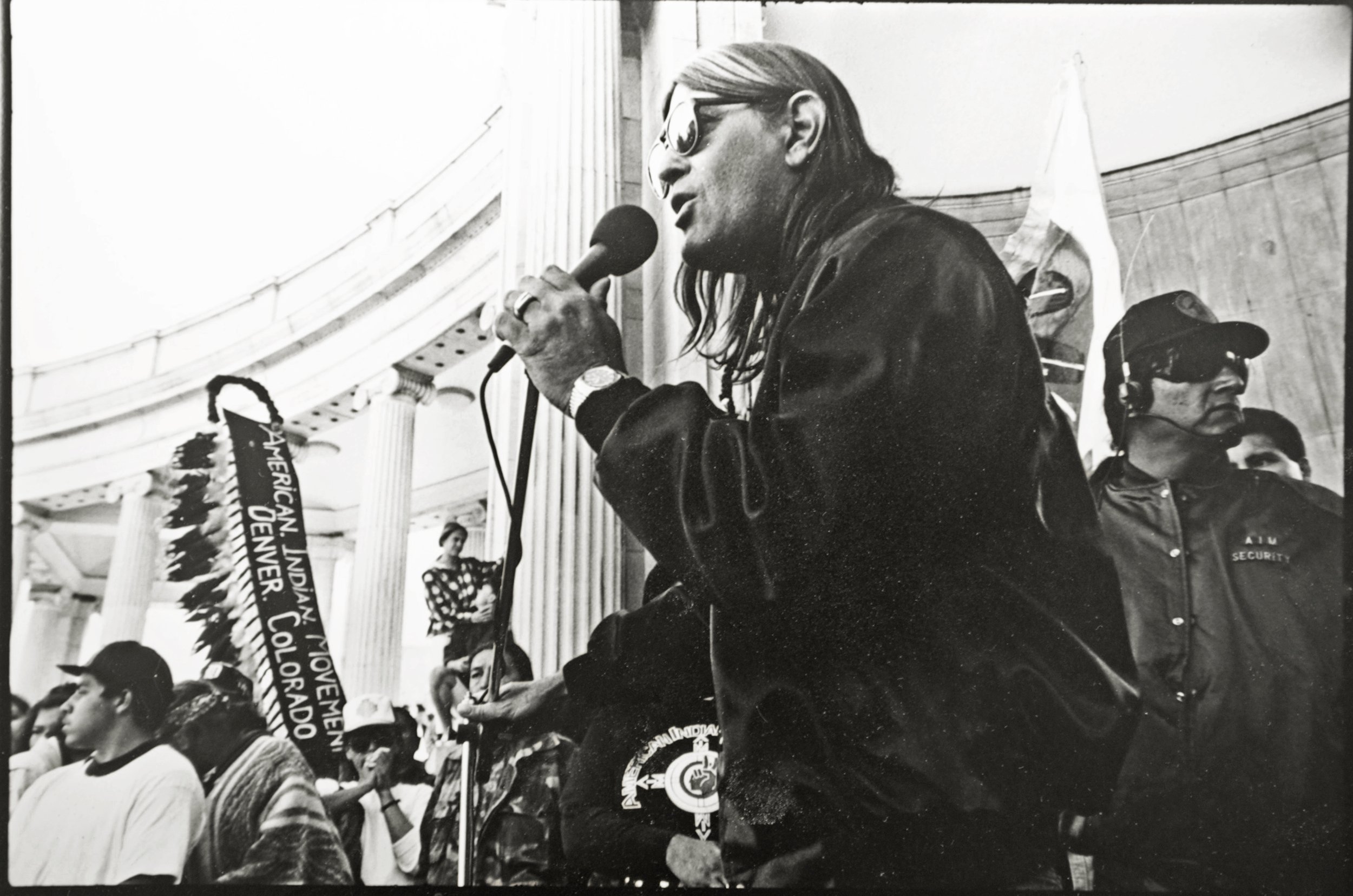

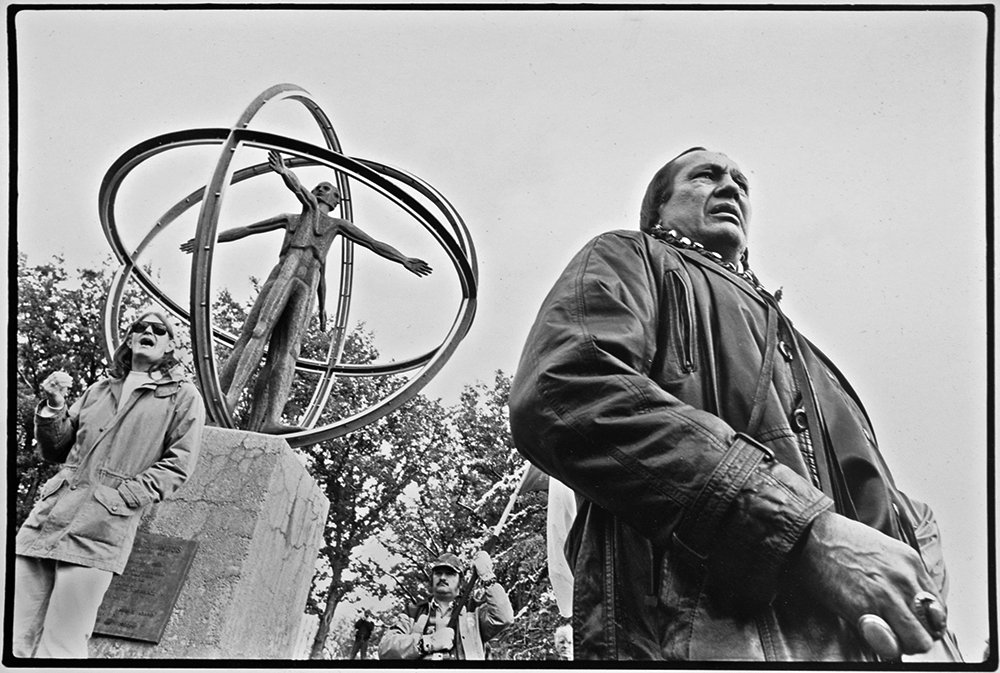

Photographing for Life on Capitol Hill, Westword, and Colorado Statesman newspapers gave him access to a full range of the ideological spectrum. As he recalled, “I went to the Kerouac conference in Boulder and stopped a guy on the street; that was William Burroughs. And there were people like Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso, Timothy Leary. I took pictures of all those guys while I was there. They had promoted themselves exceptionally well.”

“One time when I was in New Jersey, back east visiting my family, I heard that Allen Ginsberg and Leroy Jones were reading their poetry in New Jersey. I went out there, so I photographed the two of them. Leroy Jones became Amiri Baraka. Started going to the Mercury Cafe, photographing national acts that would come through. [People like Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen], Leon Redbone, Albert King, Papa John Creach. I would also go to the Botanic Gardens, to their concerts, where I photographed Gerry Mulligan. Union Station had a jazz thing, and I photographed Dizzy Gillespie over there.”

His work at demonstrations is particularly strong and shows his comfort with extreme situations. As his friend Joel Dallenbach remembers, he liked to get in close and find the heart of the action. One story John told me conveys something of that: He had read how Joel Meyerowitz approached street photography, “And one day in New York during a parade, he thought he saw Cartier-Bresson working the crowd. So he runs into another street photographer, maybe Garry Winogrand or somebody like that, and they both say each of them has seen Cartier-Bresson. So they go back to photographing. And here he is again, Cartier-Bresson, and he photographs a big drunk who starts charging at him. He throws his camera at the guy, and the guy backs off. And he retrieves his camera because it's on a wrist strap and he disappears into the crowd— another myth, developing his mystique.

Well, I found a wrist strap at a yard sale and I put it on my Leica. And one day I got out on my bicycle and started riding down the street. And I flung my camera and held my hand out, and the strap broke and the Leica tumbled down the street. It didn't survive. It wound up with a fractured case and a light leak … so enough of that.”

Denver Mud People, NYC, July 1987.

In the mid-1980s, Schoenwalter accompanied the Denver mud people to New York and made a memorable picture of them on the subway. Mark Sink remembers that, “A wonderful person called Mark Antrobus and I collaborated with a group of artists to be like the mud people we had seen in that great book by Irving Penn. Our first event was in Denver around 1980. We called it “Urban Aboriginal Week.” We started out just wearing cardboard and junk things we found. Then we started making paper pulp helmets and mudding up doing events.

“When I was living in New York in the mid-1980s, the Denver people came and we did Earth Day. We made the front page of the Daily News! Later People magazine. The New York Times picked us up. People were gathering around us, wanted to touch us. The next day we did it in Soho and they pretended we didn't exist. But people loved us at Grand Central Station.”

When I asked John about his influences, he listed William Claxton, Jerry Uelsmann, Ruth Bernhard, Sebastiao Salgado, and Mary Ellen Mark. His mention of Mark prompted another story: “I took her workshop. I traded [a print of hers] for a camera that I had, an old Graflex - Italian, leather-covered pop-up that you look down into. … I picked out a print that was used on the cover of the book that she did, “Ward 81.” Her cover picture was a woman in the bathtub. I got that one. But the one that I loved was a picture that she had taken of Federico Fellini, with a megaphone striding in Cinecittà, where they make the films. Beautiful image. And I like Fellini quite a bit.”

Perhaps his embrace of life’s diversity is best expressed in his late career passion for bird photography, which satisfied his creative needs and also provided an important stream of income. John Schoenwalter passed away after a long illness in 2019. He left his archive in the hands of trusted friends who are seeking a repository for it.

[i] Personal interview, April 2017. All direct quotes are from this interview.

Unless otherwise credited, all photographs by and courtesy of John Schoenwalter.